Was Shakespeare a spy?

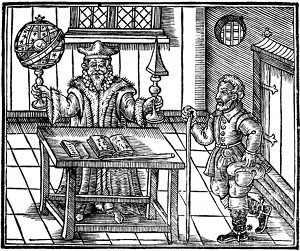

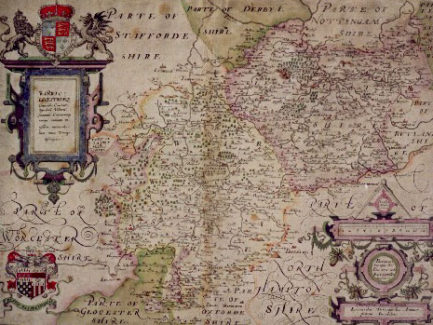

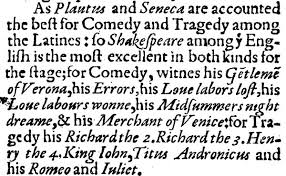

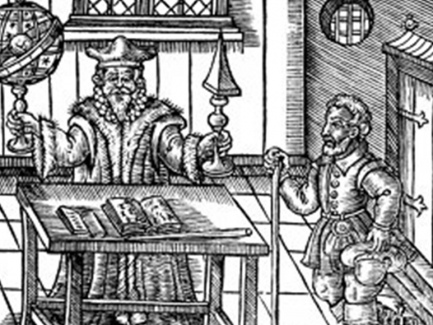

Francis Walsingham, who signed his last will and testament in December 1589, is primarily remembered as Elizabeth I’s ‘spymaster’. He established a wide-reaching system of surveillance to safeguard both the personal safety of the queen and the national security of England. His wide-reaching system of surveillance even extended into the playhouses of early modern England. Not only were the playing companies and their plays heavily censored by the Revels Office, it is also thought some of Walsingham’s spies were taken from the playhouses and the playing companies which travelled around the country.

Christopher Marlowe, an exact contemporary of William Shakespeare and one of the brightest stars of the early modern stage, was possibly one of them. His patron, Thomas Walsingham, was a relative of Elizabeth I’s ‘spymaster’ and Marlowe may have been part of the secret service operating under Walsingham. When Marlowe died in a tavern brawl in 1593, he was in the company of other people known to be employed as government spies.

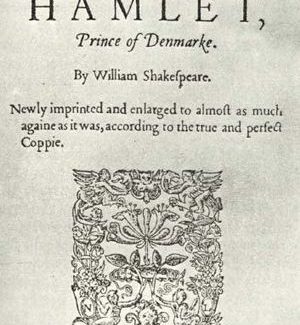

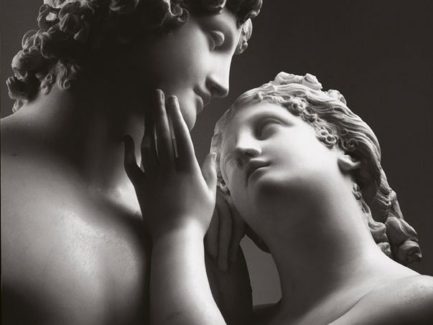

Shakespeare did not have such a colourful history, but his plays are full of spies, would-be spymasters and tricks of espionage. In The Tempest, Prospero has control over everything that happens on the island and, with the services of Ariel, he orchestrates the storm which brings his enemies to his island. Prospero’s surveillance is omniscient and he instructs Ariel to be ‘subject to no sight but thine and mine’. In Love’s Labour’s Lost, Berowne spies on his three companions and overhears them secretly declaring their love for their mistresses. Longueville and Dumaine have written love poems, despite their vows to forsake love, and the king admonishes them for their perjury. He does not, however, realise that his own protestations of love have been overheard by Berowne, who steps ‘forth to whip hypocrisy’:

BEROWNE

Ah, good my liege, I pray thee, pardon me.

Good heart, what grace hast thou, thus to reprove

These worms for loving, that art most in love?

Your eyes do make no coaches; in your tears

There is no certain princess that appears.

You’ll not be perjured, ’tis a hateful thing!

Tush, none but minstrels like of sonneting!

But are you not ashamed? Nay, are you not,

All three of you, to be thus much o’ershot?

[To Longaville]

You found his mote, the King your mote did see,

But I a beam do find in each of three.

O, what a scene of foolery have I seen,

Of sighs, of groans, of sorrow and of teen!

O me, with what strict patience have I sat,

To see a king transformed to a gnat!

To see great Hercules whipping a gig,

And profound Solomon to tune a jig,

And Nestor play at push-pin with the boys,

And critic Timon laugh at idle toys.

Where lies thy grief, O, tell me, good Dumain?

And gentle Longaville, where lies thy pain?

And where my liege’s? All about the breast:

A caudle, ho!

FERDINAND

Too bitter is thy jest.

Are we betrayed thus to thy over-view?

(Act 4 Scene 3)

© 2018 Shakespeare’s World

To read more about this topic and other events on this day in Shakespeare’s lifetime, you can see our recommendations for further reading and visit our website to buy Shakespeare’s World App or to follow us on social media.