Why was Richard II considered a dangerous play?

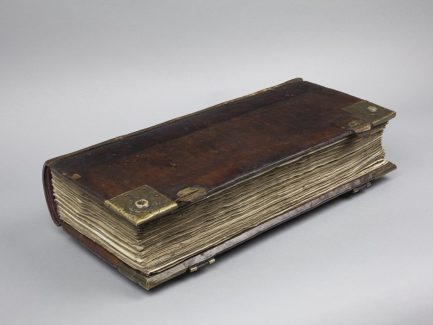

The earliest recorded performance of Richard II was on 9 December 1595. The play was performed for Sir Robert Cecil at Sir Edward Hoby’s house in Canon Row. On 7 December 1595 Sir Edward Hoby had written to Robert Cecil inviting him to supper and to see a performance of the play:

Sir, finding that you were not conveniently to be at London tomorrow night I am bold to send to know whether Tuesday may be any more in your grace to visit poor Channon row where as late as it shall please you a gate for your supper shall be open: and King Richard present himself to your view. Pardon my boldness that ever love to be honoured with your presence neither do I importune more than your occasions may willingly assent unto, in the meantime and ever resting, at your command, Edward Hoby.

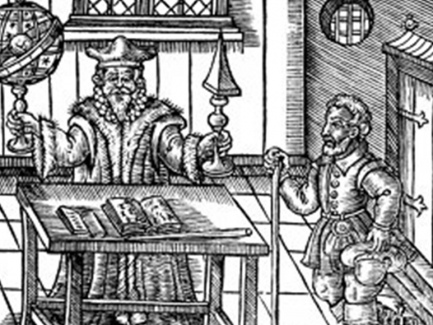

Private performances were not unusual, but as Secretary of State for both Elizabeth I and James I, Cecil monitored surveillance networks, managed intelligence operations and uncovered numerous Catholic plots and political revolts. He may have been concerned about the political implications of Shakespeare’s play about Richard II.

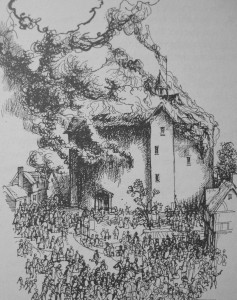

Shakespeare’s Richard II was again performed in a potentially volatile situation in 1601. It is thought that the Earl of Essex and his supporters commissioned the performance as part of a plot to rouse rebellion in the City of London. The play dramatised the forced abdication of an English king in a scene which would have been seen as politically provocative if not openly seditious. Essex had planned to lead an uprising into London on the following day and to force an audience with Elizabeth I. The performance of Richard II was intended to foster public support when he marched into London with hundreds of armed men. However, the rebellion failed, its leaders were arrested and the Earl of Essex was beheaded for treason on 25 February 1601.

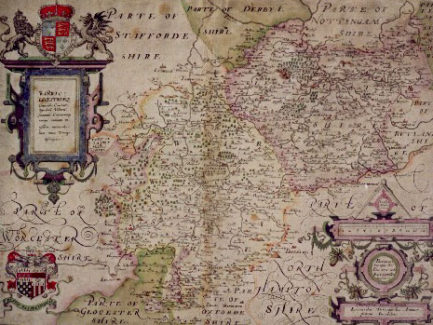

Given the similarities between Elizabeth I and Richard II, which were not lost on the queen or on audiences who saw the play, the performance of Richard II was a politically loaded event. Elizabeth I was often identified with Richard II. Like Richard II, Elizabeth had court favourites who were politically powerful, she undertook a disastrous Irish campaign, and she was faced with an uncertain succession because she would die without an heir. The queen, aware of these comparisons, was reported as saying ‘I am Richard, know ye not that?’

The actors in Shakespeare’s playing company who performed Richard II were, like the Earl of Essex’s supporters, also in danger of being arrested. Augustine Phillips, one of the shareholders of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, was called before the Privy Council to explain the performance which preceded Essex’s rebellion. Phillips managed to convince the Privy Council that the Lord Chamberlain’s Men were not involved in the rebellion. He described how the players were paid forty shillings ‘more than their ordinary’ to perform the play by Essex’s supporters. It is not difficult to see how inflammatory it would have been to stage a play about the deposition of a king at such a time, particularly when the play contained scenes in which subjects refuse to pay homage to their lawful ruler:

HENRY BOLINGBROKE

See, see, King Richard doth himself appear,

As doth the blushing discontented sun

From out the fiery portal of the east,

When he perceives the envious clouds are bent

To dim his glory and to stain the track

Of his bright passage to the occident.

DUKE OF YORK

Yet looks he like a king. Behold, his eye,

As bright as is the eagle’s, lightens forth

Controlling majesty. Alack, alack, for woe,

That any harm should stain so fair a show!

KING RICHARD II

We are amazed; and thus long have we stood

To watch the fearful bending of thy knee,

[To NORTHUMBERLAND]

Because we thought ourself thy lawful king,

And if we be, how dare thy joints forget

To pay their awful duty to our presence?

If we be not, show us the hand of God

That hath dismissed us from our stewardship,

For well we know, no hand of blood and bone

Can gripe the sacred handle of our sceptre,

Unless he do profane, steal, or usurp.

And though you think that all, as you have done,

Have torn their souls by turning them from us,

And we are barren and bereft of friends.

Yet know, my master, God omnipotent,

Is mustering in his clouds on our behalf

Armies of pestilence, and they shall strike

Your children yet unborn and unbegot,

That lift your vassal hands against my head

And threat the glory of my precious crown.

Tell Bolingbroke— for yond methinks he stands—

That every stride he makes upon my land

Is dangerous treason. He is come to open

The purple testament of bleeding war,

But ere the crown he looks for live in peace,

Ten thousand bloody crowns of mothers’ sons

Shall ill become the flower of England’s face,

Change the complexion of her maid-pale peace

To scarlet indignation and bedew

Her pastures’ grass with faithful English blood

(Act 3 Scene 3)

© 2017 Shakespeare’s World

To read more about this topic and other events on this day in Shakespeare’s lifetime, you can see our recommendations for further reading and visit our website to buy Shakespeare’s World App or to follow us on social media.